Introduction

As an island nation surrounded by seas, Japan has long held a central relationship with the ocean in its cultural, historical, and economic life. The country’s extensive coastline and rich marine resources have shaped the development, trade, and fisheries of Japanese society throughout history. However, in the contemporary era, environmental threats posed by climate change particularly sea level rise and extreme weather events have rendered Japan’s strategic relationship with the ocean increasingly critical. Issues of maritime security and ocean governance have become significant not only in environmental and economic contexts but also in terms of national security. In this regard, the policies and adaptation strategies Japan develops in response to the impacts of climate change will be vital not only for the country’s sustainability but also for regional stability.

The general framework of Japan’s historical and strategic connection with the sea

It is known that the Japanese people sometimes describe themselves as reflecting a kind of “island nation mentality” as part of their national character, which represents the belief that their society and culture, isolated by the surrounding seas, possesses a self-sufficient structure. Whether or not this is truly reflected in the character of the Japanese people, the sea plays a tremendously significant role in Japanese culture, history, society, art, and, most importantly, identity.

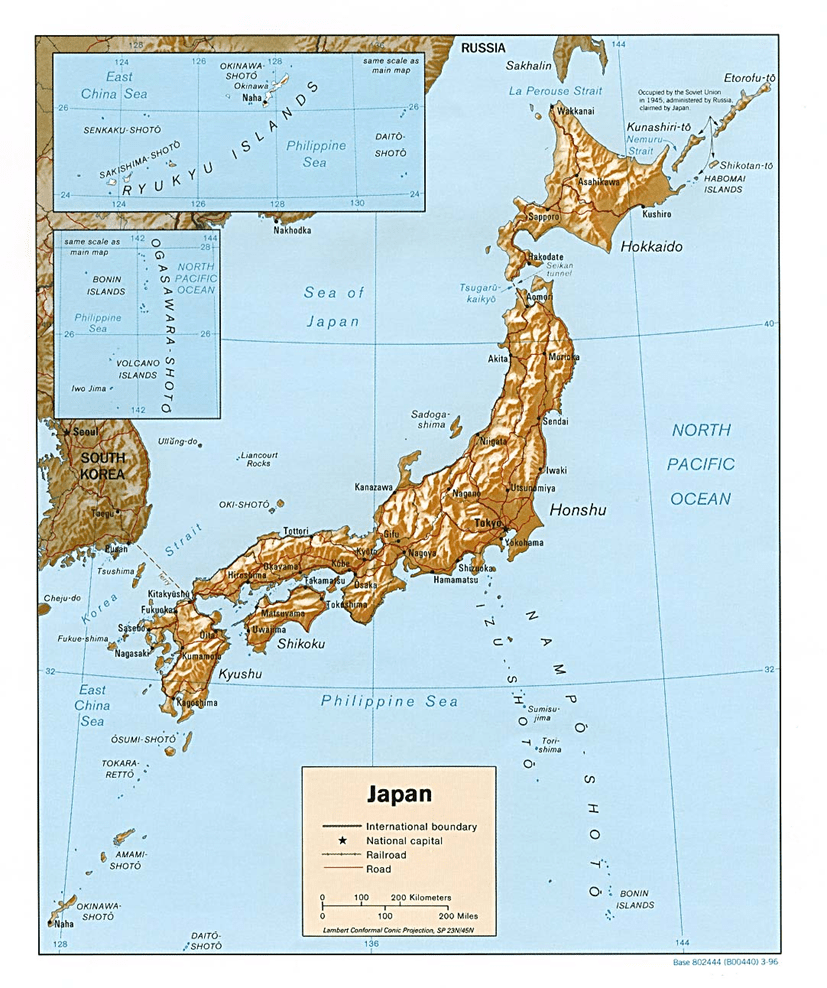

Japan is surrounded by the East China Sea, the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan, and the Sea of Okhotsk. It is known that Japan’s coastline extends over 29,740 kilometers, and moreover, no point in the country is more than 150 kilometers away from the sea. The ocean currents affecting Japan’s coasts and the climatic diversity of these waters make the region one of the most productive and biodiverse fishing areas in the world. (Bestor, 2014)

In terms of Japan and its relationship with the sea from a historical perspective, it is known that since the earliest periods, marine resources have been widely utilized in Japan. In addition to hosting a wide variety of fish species and marine life, it is also definitively known that human settlement in Japan occurred via maritime routes. Furthermore, maritime trade and travel between Japan, Korea, and China continued for over a thousand years. From the 16th century onward, Japan came into contact with seafaring European empires such as the Netherlands and Portugal; however, with the Tokugawa period, its relations with the outside world were largely restricted. This isolation lasted until the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1853, after which Japan was compelled to open its ports to foreign trade. Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan adopted Western technologies and rapidly modernized, becoming a colonial power. It strengthened its navy, expanded its trade networks, and by the early 20th century, had become a regional maritime power. (Bestor, 2014)

In terms of fishing, Japan shifted from traditional coastal fishing to large-scale offshore fishing with the onset of industrialization in the early 20th century. This transformation, supported by the state, was seen as part of Japan’s modernization process and also turned marine products into foreign exchange-earning export goods. Despite the devastation Japan experienced after World War II, it was able to quickly recover its fisheries sector. By the 1960s, it had developed modern fishing fleets operating on a global scale. However, by the 1970s, due to the depletion of marine resources and international maritime legal regulations (UNCLOS), Japan’s distant-water fishing declined. Nevertheless, the establishment of 200-nautical-mile EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) boundaries granted the country extensive maritime jurisdiction. Although Japan’s global maritime power has decreased overall, its regional maritime authority has expanded. (Bestor, 2014)

With Japan’s economic rise in the 1970s, healthy eating trends led to the popularization of sushi in the West. However, global overfishing and the 2011 earthquake along with the Fukushima disaster have negatively impacted Japanese fisheries and the reliability of its seafood. These developments indicate that Japanese marine products are facing significant ecological and commercial challenges. Although the issue of polluted water continues along the Sanriku coasts, Japan still controls one of the six most important fishing regions in the world. Along with this wealth, territorial disputes over island sovereignty between Japan and its neighbors have become more pronounced. Disagreements exist between Japan and South Korea over the Takeshima/Dokdo Island (Liancourt Rocks) in the Sea of Japan/East Sea; between Japan and China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea; and between Japan and Russia over four small islands in the southern part of the Kuril chain, located between Hokkaidō and the Kamchatka Peninsula. (Bestor, 2014)

The 200-nautical-mile zone surrounding Japan’s thousands of islands covers an area of approximately 1.73 million square miles. Possessing a wealth of resources not yet fully utilized, this zone offers, in addition to fishing potential, highly profitable opportunities through new technologies such as mineral mining from deep ocean waters, floating water turbines for electricity generation, geothermal and wind energy sources that could be found or established in Japanese waters, and the desalination of purified seawater. (Bestor, 2014)

Looking at Japan’s strategic relationship with the sea, the threats posed by current and future climate change make this relationship even more critical. Rising sea levels present serious risks to the Japanese population and infrastructure concentrated in coastal areas, and the seas remain an indispensable domain for the country’s future security and sustainability in terms of food, resources, energy, and minerals. Therefore, the sea is known to be at the center not only of Japan’s cultural and historical identity but also of its geopolitical and economic strategy. (Bestor, 2014)

Global background on the impact of climate change on maritime security

Although the term security has been defined in many different ways, in general, it refers to protecting citizens’ daily lives from various threats. One of the ways to ensure security is through maritime security. It is also important that maritime security is an integral part of maritime governance, which is one of its key characteristics.

Maritime governance is known as the concrete form of the “comprehensive management of the oceans,” which is the objective of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Among the initiatives of maritime security and security-related terms, there are development- and environment-related studies of strategic importance. It has been recognized that it is now necessary to examine policy issues that cover multiple areas such as development, environment, and security, and to determine policies to address such issues. One of the examples of how to deal with such problems is the issue of how to combat climate change. (MOD, 2021b; Komori, 2021; MOD, 2021a; UNFCCC, 1992).

What is climate change? The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which serves as an international framework for climate change, defines climate change as “a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods” (UNFCCC, 1992, Article 1, Paragraph 2).

It is known that the impacts of climate change have been extensive in the past and present, and they are expected to remain extensive in the future as well. Furthermore, how to deal with climate change has become a significant policy issue that needs to be addressed urgently and thoroughly. owever, despite these facts, climate change—which also significantly affects Japan—is often regarded primarily as an environmental and economic issue, and not as a security threat (Komori, 2021).

Nevertheless, in May 2021, Japan’s Ministry of Defense established the “Climate Change Task Force,” chaired by the Deputy Minister of Defense, to coordinate investigations across the Ministry regarding the impacts of climate change on security (Ministry of Defense [MOD], 2021a).

In addition, the 2021 Defense White Paper included a section titled “The effects of climate change on the security environment and the military.” This section explains the growing global awareness of climate change as a security threat and describes the initiatives being taken by countries around the world (MOD, 2021b).

Although the aforementioned impacts of climate change have primarily been focused on terrestrial areas, its effects are observed globally, and the ocean is no exception. In 2019, following the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published for the first time a special report specifically addressing the ocean and cryosphere, titled Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) (Ministry of the Environment, 2019).

Following the release of the SROCC, the Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation published its policy document titled Ten Recommendations based on the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere, highlighting critical points regarding ocean governance (Ocean Policy Research Institute, 2019).

According to the report, although climate change begins on land, the ocean and cryosphere, in general, regulate atmospheric and climate patterns on Earth, provide water and food, and shape economies, transportation, trade, welfare, and culture. These statements emphasize that changes occurring in the ocean lead to large-scale impacts. Alongside these consequences, the need for stronger initiatives is becoming evident. This situation demonstrates that the ocean—a space where security measures are often applied—has now become an element that must be actively protected. (Japan Forum on International Relations [JFIR], 2023)

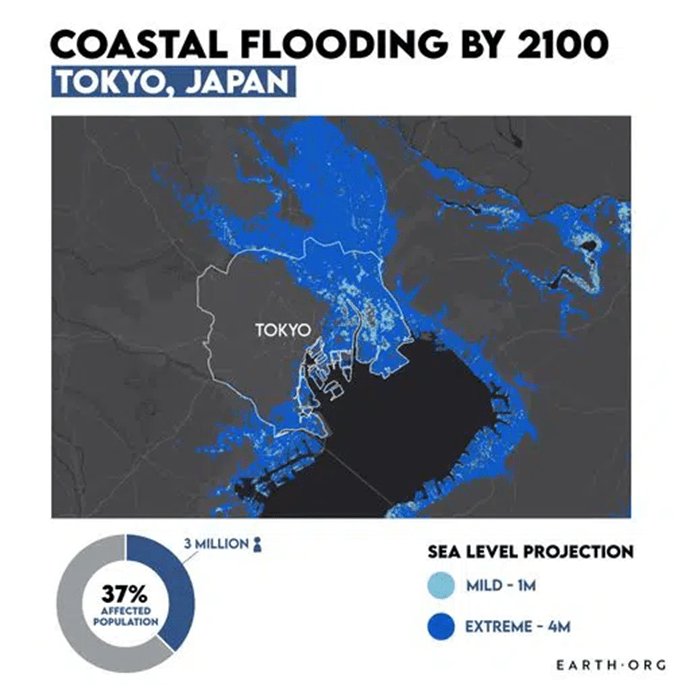

Climate change is an extremely sensitive issue for Japan, which is an island country. One of the main concerns for Japan is the rising sea levels. A potential increase of 60 cm could lead to up to a 50% rise in the population living at or below sea level in Japan’s three largest bays. These bays are known to host four of Japan’s largest cities. As a result, this situation may lead the Japanese government to reconsider flood protection systems, to reconstruct entire cities, or to relocate millions of people.

Extreme and irregular weather conditions caused by climate change will affect the entire country. Larger storm surges will threaten coastal communities that are already at risk due to rising sea levels. In inland areas, increased intensity of rainfall events can lead to extensive flooding. On top of this, higher regional temperatures increase the risk of heatstroke for Japan’s aging population, threaten food security, and are destroying the country’s coral reefs. (Koons, 2024)

Extensive low-lying land areas exist at sea level around Japan’s three main bays: Tokyo Bay, Ise Bay, and Osaka Bay. However, in the case of a 60-centimeter rise in sea level, it is estimated that both the surface area of these low-lying regions and the population living in these areas could increase by approximately 50%. This indicates that sea level rise may pose serious environmental and socio-economic threats in the coming periods. On the other hand, potential changes in the paths and intensities of typhoons may increase the risk of high wave formation in the regions bordering the Pacific Ocean. (Ministry of the Environment, Japan, 2012)

While Japan is already experiencing the impacts of climate change today, current scientific projections indicate that these effects will significantly intensify by 2050 and 2100, particularly if high-emission scenarios are followed. Environmental changes such as increasing heatwaves, prolonged agricultural droughts, and ocean acidification pose serious threats to food production, fisheries, clean water supply, and infrastructure. In addition, sea level rise, coastal erosion, and more frequent extreme weather events are rendering millions of people vulnerable to coastal flooding. In this context, it is projected that Japan could face economic losses amounting to approximately 3.72% of its GDP and damages to coastal infrastructure reaching up to 404 billion euros by 2050. On the other hand, if low-carbon policy scenarios are adopted, these impacts can be significantly mitigated in terms of both severity and economic cost; for instance, limiting global temperature rise to 2°C is estimated to reduce climate-related damages to only 1.6% of GDP by 2050. Within this framework, the implementation of holistic, climate-resilient policies holds strategic importance for maintaining Japan’s socio-economic stability. (G20 Climate Risk Atlas, n.d.)

By 2050, under the current emission scenario, the average height of extreme sea level events is expected to rise from 2.88 meters to 3.11 meters. This projection reflects a combination of indicators including the 100-year storm surge, wave setup, high tide, and sea level rise. Densely populated coastal cities such as Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Okayama are among the most affected areas, and the population exposed to annual coastal flooding is projected to increase from 3.2 million to 3.9 million by 2050. While tsunami risk is concentrated along the southern and eastern coasts, the western coast is more vulnerable to typhoon-induced storm surges.

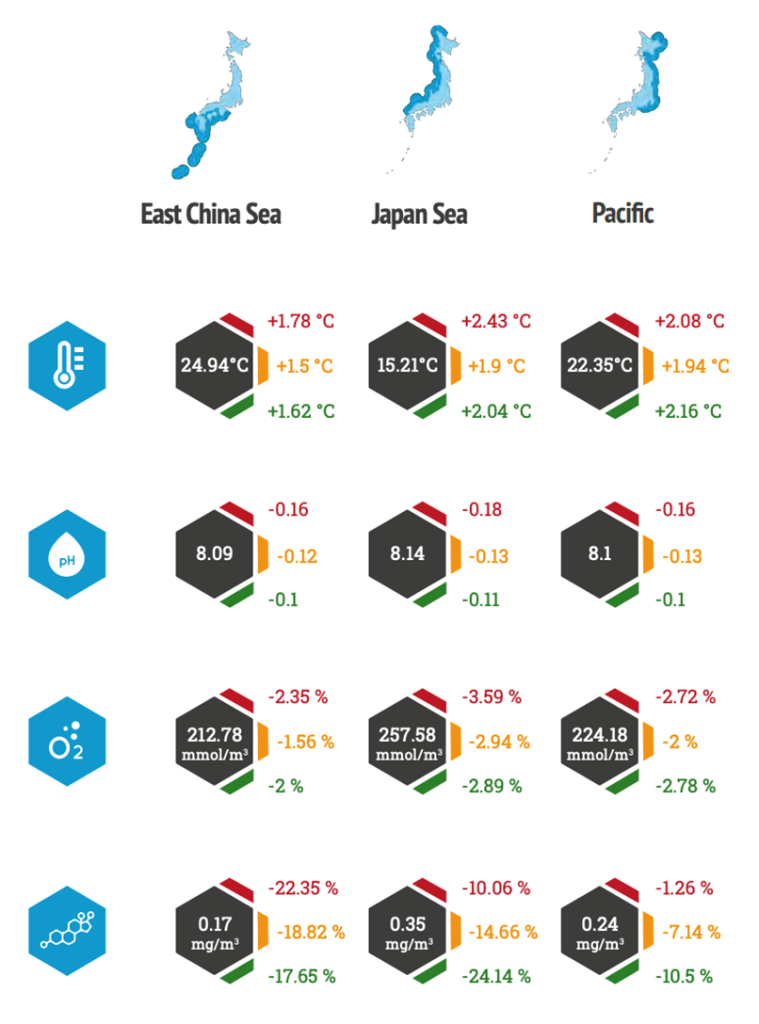

Analyses conducted in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone show that sea surface temperatures have increased by approximately 0.2°C per decade, sea water has become more acidic, and oxygen levels have decreased. These changes place significant pressure on marine ecosystems, reduce fish stocks, and threaten local economies dependent on fisheries. According to projections based on 15 different climate models, sea temperatures around Japan are expected to rise between 1.5°C and 2.4°C depending on the scenario, while pH levels will continue to decline. All these developments pose threats to marine ecosystem services and coastal infrastructure, making it imperative to maintain and enhance climate adaptation and protection measures. (Euro‑Mediterranean Center on Climate Change [CMCC], n.d.)

Japan’s Climate Commitments and Adaptation Policies

During the 2017–2018 period, Japan pledged a total of USD 20.8 billion in international financial support for climate actions, providing nearly all of this support through loans and similar instruments. The majority of these funds were directed to the Asian region, with a primary focus on mitigation. Under the Paris Agreement, Japan submitted its first Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) in 2016, aiming for a 26% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 2013 levels; this target was subsequently increased to 46% in 2021, representing a significant enhancement. Additionally, Japan fulfilled its first commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol (2008–2012) with an average annual emissions reduction of 6% compared to 1990 levels. Japan has set a net-zero emissions target by 2050 and currently accounts for approximately 2.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with a per capita CO₂ emission rate nearly double the world average. (Euro‑Mediterranean Center on Climate Change [CMCC], n.d.)

Japan has developed various policy mechanisms at national, regional, and sectoral levels to address climate change adaptation. The National Adaptation Plan adopted in 2015 includes comprehensive measures covering agriculture, water resources, natural ecosystems, coastal areas, public health, and economic activities. Moreover, Japan shares climate risk data with the public through information platforms such as A-PLAT and AP-PLAT, supporting local adaptation initiatives. Cities like Tokyo and Fukuoka have implemented their own adaptation policies to reduce local risks. In terms of energy transition, although Japan performs above the G20 average in electrification and efficiency, it still needs to make progress in increasing renewable energy capacity and reducing fossil fuel use. In 2020, 27% of total recovery expenditures were allocated to green spending, reflecting the critical role of green investments in achieving Japan’s sustainable development goals. (Euro‑Mediterranean Center on Climate Change [CMCC], n.d.)

CONCLUSION

Japan is increasingly integrating the impacts of environmental changes on maritime security into its sea policies, adapting them to these emerging realities. Environmental risks caused by climate change directly affect Japan’s economic interests and strategic security, necessitating the prioritization of environmental sustainability within maritime management and security policies. Japan’s historical connection to the seas and the significance of marine resources form key determinants of this process. In this context, harmonizing Japan’s environmental and security policies through a holistic approach is critically important for the country’s long-term stability and sustainable development. Moving forward, enhancing Japan’s adaptive capacity to new challenges arising from environmental changes and developing maritime security strategies within this framework will be decisive for the success of national policies.

- University of Texas Libraries. (n.d.). Map of Japan. Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. Retrieved June 19, 2025, from http://tinyurl.com/mub475r

- Bestor, T. C. (2014). Japan and the sea. Education About Asia, 19(2), 56. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/bestor/files/bestor_2014_eaa.pdf

- Komori, Y. (2021). Toward comprehensive climate security. In H. Sakaguchi (Ed.), Climate security: Global warming and a free and open Indo-Pacific (Part 5, Chapter 2, pp. 249–265). Tokai Education Research Institute.

- Ministry of Defense (MOD). (2021a). Summary of the minutes of the 1st Ministry of Defense Climate Change Task Force Conference. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://www.mod.go.jp/j/approach/agenda/meeting/kikouhendou/pdf/gijigaiyo_01.pdf

- Ministry of Defense (MOD). (2021b). 2021 Defense white paper: The defense of Japan (pp. 161–163). Nikkei Insatsu.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

- Ministry of the Environment. (2019). The release of the “Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere” (SROCC; Results of the 51st General Meeting) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://www.env.go.jp/press/107242.html

- Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. (2019). Ten Recommendations based on the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate and The Future of the Ocean: A Turning Point for the Ocean and Cryosphere. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://www.spf.org/global-data/opri/news_191015_IPCC_Rec.pdf

- Japan Forum on International Relations. (2023, June 8). Climate security in the oceans: The future of ocean governance in an era of climate change. https://www.jfir.or.jp/en/studygroup_article/4006/

- Koons, E. (2024, April 4). Environmental issues in Japan and solutions. Energy Tracker Asia. https://energytracker.asia/environmental-issues-in-japan-and-solutions/

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. (2012). Climate change and its impacts in Japan [PDF]. Government of Japan. https://www.env.go.jp/en/earth/cc/impacts_FY2012.pdf

- G20 Climate Risk Atlas. (n.d.). Japan. Retrieved June 19, 2025, from G20 Climate Risk Atlas: https://www.g20climaterisks.org/japan/

- Euro‑Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC). (n.d.). G20 Climate Risk Atlas: Japan [PDF]. CMCC. https://files.cmcc.it/g20climaterisks/Japan.pdf

Leave a comment