Introduction

Located on the eastern coast of Asia, South Korea has historically been positioned at the intersection of major powers. However, what makes it a strategic actor is not only this geopolitical position. South Korea also stands out on a global scale with its technological capacity, cultural influence, and active foreign policy stance. Historical disputes among South Korea, Japan, and China have at times limited the development of relations between these three countries. Nevertheless, these three countries constitute the economic, political, and cultural centers of East Asia. In this context, the continuation of efforts for cooperation despite historical issues holds the potential to contribute not only to regional development but also to global stability. The economic and political disputes South Korea experiences with Japan and China, both bilaterally and multilaterally, can be seen as a result of historical tensions, conflicting interests, and strategic competition. Evaluating these relations not only from a conflict-based perspective but also within the framework of mutual dependence and the potential for cooperation will provide a more comprehensive analysis. (Li & Park, 2022)

In terms of power status, South Korea is often classified as a “middle power.” Material indicators alone—such as military expenditures, population size, or economic capacity—are not sufficient to determine a state’s power. A state’s foreign policy behavior and how it defines itself within the international system are also decisive in understanding this status. Since the boundaries of power status are not always clearly drawn, the fact that Japan was once described as a “middle power” but is now categorized by many actors as a “great power” is an indication of this flexibility.

South Korea’s foreign policy has especially been shaped under a “middle power” strategy since 2008, and this strategy has been expressed through the concepts of “Jung-gan-ja” or “Jung-gyun-guk.” During this period, it has been observed that South Korea took steps particularly to strengthen its alliances with the United States and tended to participate in multilateral collaborations. By adopting a foreign policy approach that emphasizes the preservation of a rules-based international order, South Korea aims to contribute to the stability of regional balances. (Lee & Wiegand, 2024)

Within this strategic framework, one of the most notable foreign policy tools of South Korea is the strategy of “hedging.” This strategy, developed by middle-sized states against foreign policy uncertainties, has become a more prominent topic of discussion in the discipline of International Relations, particularly since the early 2000s when the effects of globalization intensified. South Korea uses this strategy to balance its regional and global interests. The hedging strategy has enabled South Korea to maintain a strong alliance with the United States while also preserving its economic and diplomatic ties with China. Moreover, this strategy has also laid the groundwork for efforts to develop more balanced and constructive relations with North Korea. Clearly articulated by then-President Lee Myung-bak in 2007 and implemented by subsequent administrations, this approach is a concrete reflection of South Korea’s pursuit of strategic balance among great powers. (Kılıçarslan Gül, 2023)

Chapter 1: Current Power Dynamics in East Asia

China’s Rise and Regional Influence

The People’s Republic of China has embarked on an effort to reshape the existing international order and has become a powerful rival to the United States—one of the most influential actors in the global system. China places great importance on conducting its foreign policy within the framework of regional multilateralism in an effort to gain the consent of the international community and attract other countries.

Following the events of September 11 and the 2008 financial crisis, the dominance of the U.S. in the international system began to be increasingly questioned. This period saw the emergence of rising powers, which brought about significant shifts. Among these, China’s emergence as a strong actor in the global system—marked by consistent economic growth along with military and political reforms—has contributed to a reconfiguration of the balance of power and made power transitions more evident. In the aftermath of this shift, China’s regional institutionalization efforts became more comprehensive, and the Chinese government began to gain greater influence over the structural functioning and normative frameworks of regional institutions.The concept of regionalism is regarded as one of the key prerequisites for being a powerful state in the international arena. Although regionalism is often seen as an extension of global politics, it can also be interpreted as a reaction to the pressures created by global mechanisms. When examining China’s current dominance in the global arena, it is evident that the country continues to assert its influence in line with the principles of new regionalism. China defines its approach to the concept through coexistence grounded in mutual goodwill and harmony. As a political tool of state expansion, regionalism may vary depending on the actors’ behaviors and decision-making tendencies. Tokatlı, 2022)

The Chinese government first engaged with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and later played a significant role in the establishment and functioning of other regional structures. China’s leadership role in parallel formations that exclude the United States, and its active participation in Asia-centered regional initiatives, reflect Beijing’s increasing efforts to build a China-centric political and economic network. Infrastructure projects and the allocation of financial resources stand out as core strategic tools China uses to exert influence over member states. Regional cooperation mechanisms reflect not only economic integration but also political solidarity. In this context, China aims to construct an alternative network of solidarity against the United States through platforms such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), ASEAN, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Moreover, through structures like the BRI and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), China advances its strategic interests and pursues a strategy to enhance its influence in the global system by offering alternatives to Western-centric institutions. (Tokatlı, 2022)

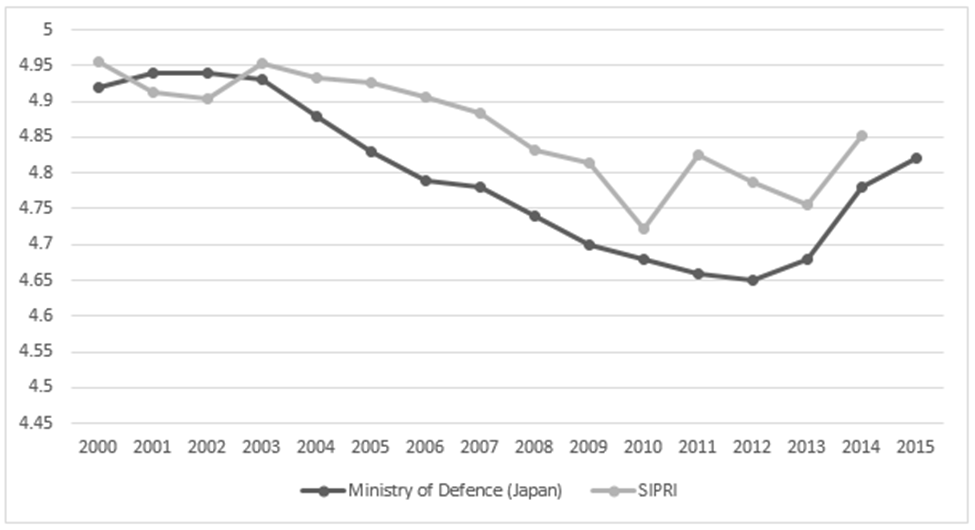

Japan’s Re-armament Process and Relations with the United States

Although many years have passed since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese people still harbor significant doubts about the benefits of military power. In May 2026, Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima, where he spoke about the horrors of using power in the nuclear age. Obama’s message and visit were largely endorsed by the Japanese people. During a time when many countries were increasingly tempted to acquire nuclear weapons, Japan stood firm against this attraction and became a strong advocate of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). (Kawakatsu, 2019)

The relationship between Japan and the United States has transformed from one of hostility in the post-war period into a strategic alliance. This alliance was formalized through a security agreement, which envisions U.S. defense assistance to Japan and the provision of bases and facilities by Japan for the U.S. military. Forming an alliance with the world’s strongest military power provided Japan with strategic protection, deterring nuclear threats from neighboring countries, and enabling it to come under America’s nuclear umbrella. In return, Japan hosts 50,000 U.S. military personnel and accommodates U.S. aircraft carriers stationed overseas. U.S. and Japanese military forces collaborate not only around the Japanese islands but also in Asia’s maritime regions, as well as in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, alongside other armed forces. Northeast Asia has become a much more contested region with China’s increasing military power and North Korea’s efforts to become a nuclear state. Japan faces growing security threats in the region due to China’s rising military activities and territorial claims over the Senkaku Islands. Diplomatic deadlock has exacerbated military tensions between Japan and China, while Russia’s military presence and North Korea’s missile program have further deepened Japan’s security concerns. In this context, the U.S. has reaffirmed its defense commitments to Japan, particularly ensuring security in disputed areas such as the Senkaku Islands. (Kawakatsu, 2019)

Japan’s security policy has undergone a noticeable transformation in response to the increasing perception of threats and regional instability. The experiences gained by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) in recent years have made it necessary for Japan to prepare for scenarios in which it might be militarily tested. North Korea’s missile tests targeting Japan, along with U.S. President Trump’s statements of support for Japan, have both increased Tokyo’s security concerns and raised doubts about the reliability of the U.S. alliance. Nevertheless, Japanese leaders continue to prioritize diplomacy over the direct use of force. In the post-Cold War era, Japan’s security preferences have continued to evolve within the framework of interpreting Article 9 of its Constitution and its alliance with Washington. While the SDF plays an active role in international cooperation, constitutional limitations on Japan’s military capabilities do not pose significant restrictions in terms of size or effectiveness. (Kawakatsu, 2019)

U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy and Its Impact on the Region

Today, China’s rise and the growing competition between the U.S. and China are primarily focused on tensions in investment, trade, and technology development. The U.S. has recently shifted its focus from the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific and Indo-Pacific regions, developing new policies aimed at balancing China’s increasing influence. In this context, alliances have been formed under U.S. leadership. In 2022, the U.S. published its Indo-Pacific Strategy document, revealing that new strategies for the regions were rapidly being established under the Biden administration.

In recent years, the U.S. has initiated efforts through QUAD and AUKUS to provide integrated deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and Asia-Pacific against China’s rising power. In this context, AUKUS offers a defense and security partnership that can be developed according to the strategic needs of the environment, based on alliance relationships. Meanwhile, QUAD has emerged as an organization in the region aimed at countering China. During the Cold War, the U.S. applied a containment policy against China and other communist states to prevent the spread of communism. Although this policy lost its influence after the Cold War, it continues in a sense through alliances developed against China. (Çokgüçlü, 2022)

South Korea’s Need for Strategic Positioning in This Context

The reshaping of the power dynamics in East Asia, framed by China’s rise, Japan’s rearmament process, and the United States’ Indo-Pacific strategies, has prompted South Korea to seek a new positioning in its foreign policy and security approaches. China’s increasing influence in the international system and its efforts toward regional institutionalization have encouraged South Korea to maintain a broad and significant partnership network, both economically and politically. Nevertheless, China’s expanding regional presence, particularly through its military modernization and involvement in contested areas such as the Senkaku Islands, constitutes a development that South Korea continues to observe with attention.

Meanwhile, the transformation in Japan’s defense policies and the deepening of its security alliance with the United States have introduced new dynamics that pose both challenges and opportunities for South Korea in the regional security environment. Japan’s moves to expand the capabilities of its Self-Defense Forces may have implications for South Korea, particularly in light of historical sensitivities surrounding the Korean Peninsula and broader regional security dynamics. Specifically, in the face of North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile capabilities, South Korea maintains and strengthens its alliance with the United States, while cautiously exploring limited cooperation with Japan in the security sphere. The U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, encompassing frameworks such as QUAD and AUKUS aimed at balancing China’s regional influence, requires South Korea to navigate complex strategic decisions regarding its role in this evolving security architecture. South Korea strives to preserve its robust economic relations with China while concurrently supporting U.S.-led regional deterrence policies and enhancing its alliance commitments. The effort to balance these priorities has emerged as a central pillar of South Korea’s foreign policy orientation. (Çokgüçlü, 2022)

Chapter 2: South Korea–China Relations

Despite geographical proximity, cultural affinities, and historical ties between South Korea and China, their bilateral relations did not fully normalize even after the end of the Cold War. The legacy of the Cold War’s Iron Curtain and the Korean War largely prevented direct contact between the two countries. China’s close relations with North Korea and South Korea’s ties with the United States and Taiwan further reinforced this divide. Until the late 1970s, exchanges between the two countries were limited to sports, academic, and postal interactions. Economic ties were confined to indirect trade through third-party countries such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan. A turning point came when China initiated economic reforms and began opening up to the outside world. For South Korea, developing better relations with Beijing was seen not only as a gateway to China’s vast market but also as a strategic opportunity to leverage China’s influence over North Korea in pursuit of peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula (Ye, 2017).

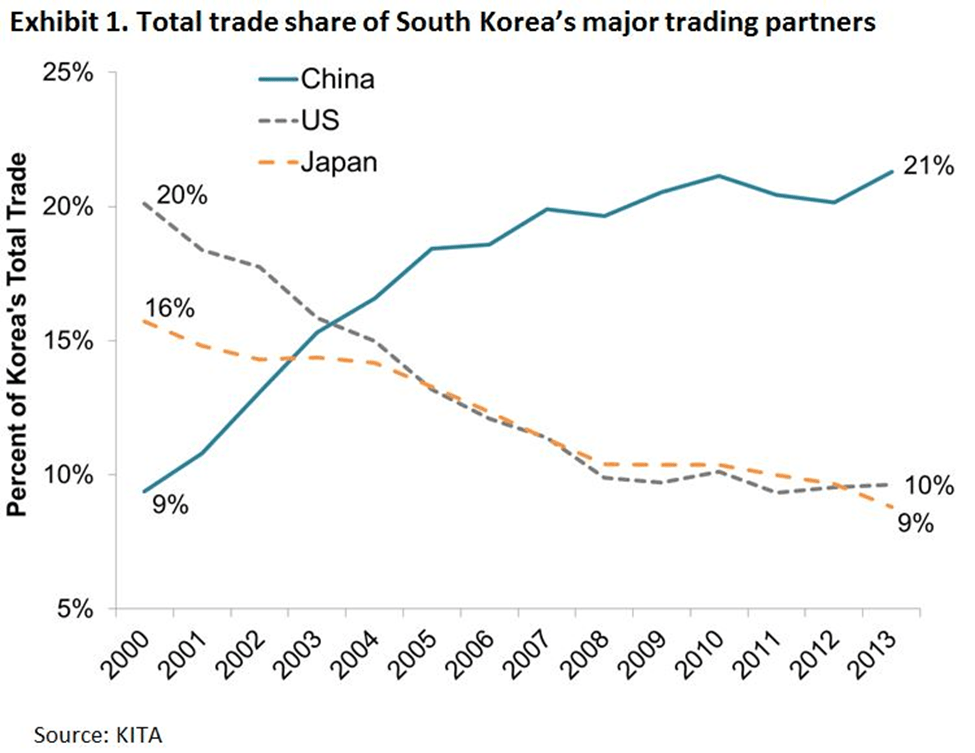

Relations began to accelerate gradually after 1985, when China’s trade volume with South Korea surpassed that with North Korea. By 1987, South Korea had become China’s seventh-largest trading partner. In 1990, just two years after China allowed direct investment from South Korea, it had received over $16 million in investment, with more than 7% of South Korea’s total overseas direct investment flowing into China. These economic ties paved the way for broader exchanges in other areas and between the two governments. Nevertheless, China’s ties with North Korea and South Korea’s relationship with Taiwan remained significant barriers to diplomatic recognition. It has been reported that Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping wanted to normalize relations with South Korea as early as 1985, but concerns about Pyongyang’s response delayed this process until the end of the Cold War. As a result, China was the last communist country to officially recognize South Korea (Ye, 2017).

In 1992, the two countries officially established diplomatic relations. Since normalization, bilateral trade has increased 55-fold, reaching $290 billion by 2014. China has become one of South Korea’s largest trading partners, its biggest export market, its largest source of imports, and the top destination for South Korean students and travelers abroad. Initially described in 1992 as a “friendly cooperative relationship,” the partnership advanced to the level of an “enhanced strategic cooperative partnership” by 2014. China and South Korea have also worked together through bilateral and multilateral platforms such as APEC, the United Nations, ASEAN+3, and the China–Japan–South Korea trilateral summit. Despite steady progress in economic ties, political relations have experienced dramatic fluctuations over the past two decades. One of the primary sources of tension has been North Korea. Although China and South Korea share common interests in maintaining regional peace and stability, they have fundamentally different strategies toward Pyongyang. These differences became especially evident following the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan in March 2010 and North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island a few months later. These events created serious problems in bilateral relations, and the long-term trend in the 21st century has pointed to a general decline in political ties (Ye, 2017).

Moreover, tensions between China and South Korea frequently arise from a wide range of issues, including media representations, disputes over historical narratives, maritime jurisdiction violations, and symbolic acts of protest. While such events may seem minor at a societal level, they often have the potential to cause significant diplomatic tensions between the two nations (Ye, 2017).

In the last two decades, China’s rapid economic growth has profoundly reshaped the domestic politics and foreign policy strategies of both countries. A recent example is the 2017 THAAD crisis. When the United States deployed the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system in South Korea, China perceived this move as a threat to its own strategic security and responded with economic and diplomatic sanctions against South Korea. Currently, the U.S. plans to deploy THAAD in Israel to counter hypersonic missile threats such as those from Iran, and this signals the possibility of more advanced versions of the system being stationed in East Asia in the future. Such developments may heighten China’s sensitivity regarding regional security balances and prompt renewed pressure on South Korea. In this context, what happens in the Middle East could directly impact South Korea’s diplomatic positioning as a response to China’s interpretation of U.S. defense strategies (Al Jazeera, 2024).

Overall, the China–South Korea relationship has evolved into a complex interaction between a rising global power and a developing middle power.

Chapter 3: South Korea–Japan Relations

South Korea–Japan relations have undergone multilayered and structural transformations since the post-World War II era, marked by historical grievances and identity conflicts that have contributed to a complex diplomatic landscape. These relations can be analyzed chronologically in three main phases. The first phase, referred to as the “1.0 system,” emerged in the context of liberation from colonial rule and the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations. Despite the détente of the 1970s and the “New Cold War” developments of the 1980s, this framework remained the foundational structure of bilateral ties (Choi, 2023).

The “2.0 system” took shape following the end of the Cold War, South Korea’s democratization, and political changes in Japan. Institutionalized through the 1998 Joint Declaration, this phase saw improved relations symbolized by co-hosting the 2002 FIFA World Cup and the global spread of Korean popular culture, known as the “Korean Wave” (Hallyu). However, the geopolitical landscape began to shift after 2010, particularly with China surpassing Japan in GDP, altering regional power dynamics. This gave rise to a new phase known as the “3.0 system,” which has since entered a cycle of trial and error. Relations reached historic lows, exacerbated by deep-seated structural crises (Choi, 2023).

A key flashpoint in this period has been the issue of “comfort women,” referring to the system of military sexual slavery operated by the Imperial Japanese Army between 1932 and 1945. Despite the 2015 agreement claiming to be a “final and irreversible resolution,” trust deficits persisted. Tensions escalated further with the 2018 ruling by South Korea’s Supreme Court on forced labor, followed by the near-termination of the GSOMIA agreement, trade restrictions, and increasingly negative public perceptions on both sides (Nam, 2021; Son, 2018; Kil, 2019; Choi, 2023). The term “comfort women” refers to one of the largest incidents of human trafficking and sexual exploitation in modern history. While this euphemism has drawn criticism for downplaying the gravity of the crimes, it remains widely used in international discussions, historical research, and legal documents. Hence, this study adopts the term for consistency. Though the exact number of victims is unknown, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of women were subjected to this system. The majority came from Korea and China, with others from Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and even European women in occupied territories (Asian Studies, 2024).

Beyond historical grievances, divergences in identity and strategic orientation have also been central to the crisis. Japan’s inclination toward historical revisionism and growing criticism in South Korea of the “1965 System” have intensified disputes over the interpretation of war crimes and memory politics (Park, 2022; Choi, 2023). Moreover, Japan’s hardline stance toward China contrasts with South Korea’s occasional diplomatic rapprochements with Beijing, deepening the sense of “geopolitical insecurity” (Lee, 2019; Kil, 2019).

Since President Yoon Suk-yeol took office in 2022, his administration has sought to improve relations with Japan through a “future-oriented” approach. However, this policy has faced strong domestic criticism. The foundation established in 2023 for compensating forced labor victims has been weakened by the absence of participation from Japanese companies. Furthermore, Japan’s move to nominate the Sado gold mine for UNESCO World Heritage status while denying the use of forced labor during wartime has heightened public discontent in South Korea. Ultimately, the tensions of the past decade stem not only from diplomatic missteps but also from underlying structural issues related to identity, power balance, and strategic divergence. A lasting and stable framework for South Korea–Japan relations can only be achieved through historical reconciliation and the restoration of mutual trust. (East Asia Forum, 2024).

Chapter 4: The Balancing Strategy in the Context of South Korea’s Foreign Policy

After the Second World War, a significant number of new states emerged, particularly in Africa and Asia. In Southeast Asia, the ratio between great powers and small states shifted during this process, and the sudden increase in the number of newly formed states attracted the attention of International Relations (IR) scholars. Therefore, in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a growing number of studies focusing on rising states. Since most states do not fall into the category of great powers, and especially after the end of the bipolar system following the Cold War, it has become necessary to classify smaller powers based on their capacities and influence in the international system. Middle power theory distinguishes states that have sufficient capacity to pursue their national interests by standing up to great powers and acting independently from those with less capacity and struggling for survival (Kılıçarslan Gül, 2023).

Foreign policy behaviors traditionally associated with middle power diplomacy have generally been expressed as balancing and bandwagoning. However, the complex nature of globalization has created a need for new concepts to explain these behaviors. Therefore, scholars in the field of International Relations have developed concepts such as hedging, bonding, transcending, and hiding to explain middle power behaviors.South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, who took office in December 2007, defined his country as a “middle power” and stated that South Korea would conduct middle power diplomacy to contribute to regional and international peace and security. In this context, South Korea’s middle power diplomacy is considered relatively new (Kılıçarslan Gül, 2023, p. v).

President Lee was aware that managing the North Korean threat and sustaining regional middle power diplomacy required the support of both the United States and China. Therefore, he defined relations with the United States as a “strategic alliance” and with China as a “strategic partnership,” focusing on establishing balanced relations with both countries. In order for South Korea to maintain both its alliance with the United States and its partnership with China, a new foreign policy strategy called “hedging” was needed. South Korea is a significant regional actor due to its contributions to regional peace and stability, and a global actor due to its economic development. Therefore, understanding South Korea’s foreign policy strategy in the context of the China–U.S. great power rivalry is of great importance. This is because South Korea is simultaneously allied with the United States and partnered with China. In this case, the “hedging” strategy provides an appropriate framework for defining South Korea’s foreign policy vision, which is caught between the U.S. and China (Kılıçarslan Gül, 2023, p. v).

Conclusion

Power balances in East Asia are shaped by constantly changing international and regional dynamics. In this context, South Korea is at the center of a carefully maintained balance policy between China and Japan, both geographically and geopolitically. While the expansion of China’s economic influence increases its determinative power over regional policies, the transformation in Japan’s defense policies—along with historical issues—affects the course of bilateral relations. At the same time, the United States’ strategic approach toward the Indo-Pacific region is among the elements that directly affect South Korea’s foreign policy preferences. South Korea’s relations with China largely develop within the framework of economic cooperation. However, this relationship has a multidimensional character due to regional security issues and strategic sensitivities. In relations with Japan, historical legacy, public perceptions, and security policies continue to be decisive. Although relations with both countries are occasionally marked by tensions, the pursuit of dialogue and cooperation continues in various areas.

Under current conditions, South Korea builds its foreign policy on balance in line with the strategic responsibilities it faces. In response to regional developments, a flexible, cautious, and multi-faceted diplomacy is preferred; an attempt is made to balance national interests with international obligations. In this process, economic integration, security cooperation, and diplomatic contacts hold an important place among South Korea’s foreign policy tools. The multidimensional and variable nature of developments in the region creates a ground that affects South Korea’s strategic position in terms of both opportunities and challenges. Therefore, every step taken has the potential to directly affect not only bilateral relations but also the overall power distribution in East Asia.

- Li, Y., & Park, C. (2022). Strengthen China-Japan-South Korea (CJK) trilateral cooperation: Effective management of historical conflicts. New Asia, 29(4), 41–65.

- Lee, S., & Wiegand, K. E. (2024). South Korea’s strategy toward the US–China rivalry. Journal of East Asian Studies, 24, 305–323.

- Kılıçarslan Gül, E. (2023). South Korea’s foreign policy: The hedging strategy (Yüksek lisans tezi). Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü. https://hdl.handle.net/11511/104857

- Tokatlı, S. G. (2022). Uluslararası sistem içerisinde Çin’in artan bölgesel etkinliği ve paralel kurumsallaşma girişimleri. Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları Dergisi, 2(1), 58-74.

- Kawakatsu, H. (2019). Japan’s rearmament and relations with the United States. University of California Press. https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=tr&lr=&id=LNKGDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=japan+rearmament+and+usa&ots=Souxo7Lan8&sig=HMqFKPxnT_DZ_L1nMhBrs_lNLUE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=japan%20rearmament%20and%20usa&f=false

- University of Malaya. (n.d.). Shinzo Abe’s security policy: A departure from defensive posture. Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://aei.um.edu.my/shinzo-abe-rsquo-s-security-policy-a-departure-from-defensive-posture

- Çokgüçlü, Y. (2022). Asya Pasifik ve Hint Pasifik’te ABD öncülüğünde geliştirilen ittifakların (AUKUS- The Quad) ABD-Çin ilişkilerine etkisi. International Journal of Social Sciences.

- Ye, M. (2017). China–South Korea relations in the new era: Challenges and opportunities. Lexington Books. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=tr&lr=&id=_TAmDwAAQBAJ

- Al Jazeera. (2024, October 15). What is the THAAD anti-missile system that the US is sending to Israel? Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/15/what-is-the-thaad-antimissile-system-that-the-us-is-sending-israel

- Asian Studies. (2024). Teaching about the ‘Comfort Women’ during World War II and the use of personal stories of the victims. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/teaching-about-the-comfort-women-during-world-war-ii-and-the-use-of-personal-stories-of-the-victims/

- Choi, H. (2023). Korea-Japan Relations during the Period of US-China Strategic Competition: Polarized Politics and South Korea’s Policy toward Japan. Seoul Journal of Japanese Studies, 9(1), 83–122. https://keia.org/publication/korea-japan-relations-during-the-period-of-us-china-strategic-competition/

- East Asia Forum. (2024, September 12). Historical memories haunt South Korea-Japan relations. https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/09/12/historical-memories-haunt-south-korea-japan-relations/

- Kil, Y. (2019). Strategic Tensions in East Asia.

- Lee, W.-D. (2019). Structural Changes in East Asian Diplomacy.

- Nam, K. (2021). Korea-Japan Relations in Transition.

- Park, C. H. (2022). Korea’s Strategic Identity.

- Son, Y. (2018). Security and Identity in Korea-Japan Relations.

- Kılıçarslan Gül, E. (2023). South Korea’s Foreign Policy: The Hedging Strategy (Yüksek lisans tezi, Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi, Uluslararası İlişkiler Bölümü).

- Peterson Institute for International Economics. (n.d.). South Korea’s Faustian dilemma: China-ROK economic and security ties. Retrieved from https://www.piie.com/blogs/north-korea-witness-transformation/south-koreas-faustian-dilemma-china-rok-economic-and

Leave a comment