Written by Zuzanna Piotrowicz

Zuzanna Piotrowicz (born in 2000) holds a Bachelor’s degree in Latin American Studies and is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in International Relations at Jagiellonian University in Cracow. Her Master’s thesis explores the role of Indigenous communities in the Amazon within the global environmental dialogue, aligning with her academic focus on socio-environmental justice in South America and the resistance of Indigenous peoples to extractivist projects. In 2024, she participated in a bilateral exchange program at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Peru in Lima, during which she spent a week in Madre de Dios as part of a rainforest conservation course. Zuzanna is a co-organizer of the annual “Latin American Culture Days” international conference at Jagiellonian University and has written two academic articles examining the impact of the governments of Jair Bolsonaro and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva on the Brazilian Amazon. She is fluent in Spanish and is learning Portuguese.

Introduction – What is the Deal About?

On December 6th 2024, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and head of states from four Mercosur countries (Brazilian President Lula da Silva, Argentinian President Milei, Paraguayan President Peña, and Uruguayan President Lacalle Pou) finalised negotiations for a EU-Mercosur partnership agreement that had been ongoing, with interruptions, since 1999. The document consists of three main parts: trade, political dialogue, and sectoral cooperation (including areas such as migration, digital economy, and human rights). It eliminates 93% of Mercosur tariffs on EU goods and provides preferential treatment for the remaining 7%. Additionally, 91% of EU tariffs on goods from Mercosur are removed1. This means that the EU will allow greater imports of beef, poultry, sugar, and other agricultural goods from South America, while securing increased exports of cars, plastics, machinery, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, among other things.

Although an agreement was reached in principle, the final texts of the deal have not yet been completed, signed, or ratified, meaning the agreement has not come into effect. If ratified, it would become the largest trade agreement for both the EU (449 million inhabitants) and Mercosur (260 million inhabitants) in terms of the number of citizens involved. However, concerns remain over potential environmental and social impacts, particularly in the Amazon. The new agreement is causing great controversy in the context of possible deforestation, biodiversity harm and threat to indigenous communities in a region that has been facing these challenges for decades.

The New 2024 Arrangements

Although the agreement was tentatively reached in 2019, it was strongly criticised at the time by civil society for a number of reasons, most of which focused on the issue of insufficient environmental safeguards2. In October 2020, the European Parliament and trade commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis concluded that the agreement in its current form could not be approved3. Thus, in 2023 and 2024 new rounds of negotiations were held to discuss an additional instrument – the EU called for stronger commitments on complying with the Paris Agreement and preventing deforestation. In the end, modifications were made to the content of the text, although the chapters on agriculture and standards for production related to health and the environment remained unchanged.

The new agreement includes a range of additional commitments on sustainable development, highlighting the Paris Agreement as a fundamental reference point for both the EU and Mercosur and obligating both parties to adhere to its provisions4. It also introduces specific commitments to halt deforestation, with a focus on protecting forests, particularly the Amazon. In terms of labor standards, the agreement contains enforceable commitments to uphold labor rights and ensure the sustainable management of natural resources. To safeguard against an excessive influx of goods under market liberalization, the parties have agreed on enhanced protective mechanisms, as well as improved procedures for dispute resolution. Additionally, the agreement aims to facilitate the development of stable supply chains, including critical raw materials essential for the green transition. A review clause was also introduced, allowing for amendments to the agreement for the first time three years after it comes into force.

Insufficient Environmental Guarantees

While the new provisions undoubtedly emphasise conservation, the possibility of real enforcement – particularly in the Brazilian interior – is highly questionable. The Paris Agreement clause in the deal has limited applicability, as it only applies if one party withdraws from the Agreement, making its effectiveness questionable. Its formulation is weaker than similar clauses in other EU agreements, and its enforceability is further complicated in the context of Mercosur, where entire regional blocs are involved. The suspension of the entire agreement in the event of a violation is politically unlikely, and partial suspension would be technically challenging. The credibility of the commitment is also questionable, especially considering actions such as the withdrawal of Argentinian negotiators from COP29, which undermines trust in the obligations. Regarding deforestation, the commitment to halt it by 2030 is vague and non-binding, and there are no enforceable sanctions for violations of sustainability provisions, including those related to deforestation. The agreement does not align with the EU’s most recent commitments to integrate sustainable development into trade policy. While the deal is intended to be considered when assessing deforestation risks in Mercosur countries, it is likely to underestimate the actual threat in the pursuit of economic gain.

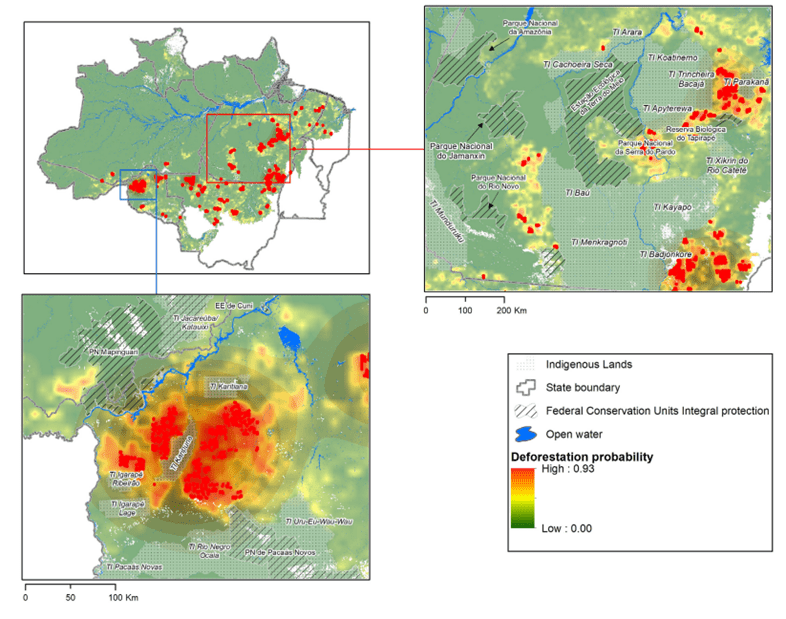

Moreover, studies have shown that the agreement will lead to increased deforestation in South America, regardless of the circumstances5. Deforestation in Mercosur countries could rise by between 122,000 and 260,000 hectares, while in Brazil alone, additional deforestation could reach up to 173,000 hectares, exceeding the European Union’s annual deforestation footprint. Most of this increase will be linked to cattle being displaced from land taken over for agricultural expansion. Also, numerous regions most vulnerable to deforestation driven by the agreement are located next to indigenous territories (Fig. 1). The Brazilian government’s ongoing efforts to weaken protections for these areas are making it increasingly difficult for indigenous communities to defend their lands against encroachment and deforestation.

Figure 1 – Deforestation pressure in the Amazon

The threat of further deforestation is most severe in regions that have recently experienced high levels of forest loss, particularly in the eastern and southern parts of the Brazilian Amazon biome, including the states of Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia. This risk is expected to rise along the borders of numerous indigenous territories, especially in the states of Pará and Rondônia.

In other research examining the impact of trade agreements across 189 countries over a 10-year period, it was found that the most significant deforestation linked to trade liberalization occurs within the first three years after an agreement takes effect6. This sharp and statistically significant rise in deforestation coincides with an increase in the conversion of land for agriculture. Some proponents argue that the additional deforestation and environmental pressures caused by the free trade agreement will be offset by the provisions in the trade and sustainable development chapter; however, the evidence suggests that the current chapter is inadequate to address these risks, and it will remain insufficient unless strong environmental protections are established before the deal is implemented.

Possible Indigenous Impact

It should be explained though, how exactly the deforestation is linked to the well-being of indigenous peoples. The destruction of forests displaces communities, undermines their self-sufficiency by depleting essential resources such as food and medicine, and disrupts traditional practices that are vital to their cultural identity. Additionally, deforestation accelerates climate change, causing unpredictable environmental patterns that jeopardize indigenous agriculture and subsistence activities. The influx of illegal activities and infrastructure development further exposes these communities to health risks, violence, and the violation of their rights.

Furthermore, the expanding trade in critical raw materials – necessary in the European so-called „green transformation” – presents serious risks of exacerbating human rights violations, environmental damage (including water scarcity and pollution) and public health concerns. Many of the world’s energy transition mineral projects are situated on or near land inhabited by indigenous peoples7, posings severe consequences for them. It is not rare for indigenous groups to lose access to their traditional territories, fundamental to their culture and way of life, particularly in the Amazon, because of extractivist projects8. Those who oppose this kind of activities, including indigenous community leaders, are often subjected to violence by private companies, governments, and military forces9. The extractive industry also contributes to the concentration of wealth in the hands of corporations, leaving local communities impoverished and deprived of essential resources such as land, forests, and water. Mercosur countries are rich in reserves of lithium, copper, and other minerals, yet the agreement does not address the International Labour Organization no. 169 Convention10, or the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People11. Both pieces of legislation include the institution of so-called consulta previa – prior consultation. The right to prior consultation, which is in line with the concept of ethno-development and inclusiveness, provides a mechanism for including indigenous communities in the decision-making process for the implementation of projects that may affect them (this therefore applies primarily to projects in indigenous territories – including mining projects). Despite the significant impact of trade agreements on people’s daily lives, land, and security, this deal was crafted behind closed doors with an unprecedented lack of transparency12. No consultation with local communities or indigenous peoples occurred, even though they are the foremost protectors of the forests. The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), Brazil’s indigenous umbrella organization, has openly opposed the agreement, arguing that it poses a threat to their land and is based on an economic model that inherently harms them13. While the EU-Mercosur agreement may offer economic benefits from access to raw materials, it remains uncertain whether these benefits will be realized in a safe and sustainable manner, especially if the interests of local communities and environmental protection standards are not properly addressed.

Additionally, Ms. Ursula von der Leyen in her speech highlighted the importance of preserving the Amazon, referring to it as an „extraordinary heritage” that the agreement aims to respect14. Supporters of the deal have argued that the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) will help mitigate negative consequences. However, the EUDR does not provide adequate protection for other critical ecosystems, such as Brazilian Cerrado, which has become Brazil’s new deforestation frontier15. The focus on the Amazon in the speech, while overlooking other important ecosystems, is significant. The increased imports of agricultural commodities into the EU could possibly lead to further deforestation in this area, and its indigenous communities face considerable threats as a result of this gap in regulation.

Conclusion

There is little reason to believe that the new arrangements, which commit countries to uphold the Paris Agreement and address deforestation, will have any meaningful impact on the ongoing environmental crisis in Brazil. In fact, since the 2019 in principle agreement, numerous key environmental protections in Brazil have been dismantled – mainly through the then president, the climate denialist Jair Bolsonaro, whose rule had a devastating impact on the country’s rainforests. These included efforts to open indigenous lands to mining and agribusiness, the exclusion of civil society and experts from environmental forums, the erosion of transparency regarding deforestation and fire alerts, and the freezing of $1.2 billion in the Amazon Fund. Although the country regained its position in the global environmental dialogue when Lula da Silva took power in 2023, many of his administration’s actions are still controversial (such as passing of the infamous so-called Marco temporal bill)16 and the radical measures implemented by his predecessor cannot be reversed overnight. The mechanisms of land grabbing and violence in the Amazon have a long and complicated history, and the solution to these problems remains beyond the reach of central authority. There is no doubt that the new agreement with the European Union will open the way for even more intensive exploitation of Amazonian territories, and the vain promises to stop deforestation have no real chance of being fulfilled in Brazil’s socio-environmental reality.

- 1European Commission, EU-Mercosur: Text of the agreement, 2024. https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur/eu-mercosur-agreement/text-agreement_en [accessed: 02.03.2025].

- 2Friends of the Earth Europe, EU-CELAC summit: 450+ organisations call to stop toxic EU-Mercosur deal, 2023. https://friendsoftheearth.eu/press-release/eu-celac-450-organisations-call-stop-toxic-eu-mercosur-deal/ [accessed: 02.03.2025].

- 3European Parliament, Committee on International Trade, Hearing of Valdis Dombrovskis, 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/files/commissionners/valdis-dombrovskis/en-dombrovskis-verbatim-report.pdf [accessed: 02.03.2025], European Parliament, European Parliament resolution of 7 October 2020 on the implementation of the common commercial policy – annual report 2018, 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0252_EN.html [accessed: 02.03.2025].

- 4European Commission, EU-MERCOSUR Partnership Agreement – Trade and Sustainable Development, 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/880029/Factsheet%20EU-Mercosur%20Trade%20Agreement%20-%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf [accessed: 02.03.2025].

- 5F. Taheripour, A. H. Aguiar, The impact of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement on land cover change in the Mercosur region, [in:] Instituto do Homem e Meio Ambiente da Amazônia, Is the EU-Mercosur trade agreement deforestation proof?, Belém 2020.

- 6R. Abman, C. Lundberg, Does Free Trade Increase Deforestation? The Effects of Regional Trade Agreements, „Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists” 2020, vol. 7, n. 1.

- 7J. Owen et al., Fast track to failure? Energy transition minerals and the future of consultation and consent, „Energy Research & Social Science” 2022, vol. 89.

- 8Neoliberal extractivism refers to an approach to natural resource management that is focused on maximising profits through the extraction of raw materials, usually without sufficient attention to long-term social and environmental impacts. In this model, which is gaining popularity in many Latin American countries, governments often offer investment incentives to multinational corporations in exchange for minimal environmental and human rights standards.

- 9Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, Mapping of the violence in the Amazon region: final report, 2022. https://forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/violencia-amazonica-ingles-v3-web.pdf [accessed: 02.03.2025].

- 10International Labour Organization, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169, 1989.

- 11United Nations, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007.

- 12Friends of the Earth Europe, A 10-point peek behind the curtain, 2024. https://friendsoftheearth.eu/publication/eu-mercosur-lost-transparency/ [accessed: 03.03.2025].

- 13P. Blenkinsop, EU-Mercosur trade deal threatens Indigenous lands, activist says, Reuters, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-mercosur-trade-deal-threatens-indigenous-lands-activist-says-2023-06-29/ [accessed: 03.03.2025].

- 14European Commission, President Ursula von der Leyen’s remarks during the Mercosur Summit in Montevideo, Uruguay, YouTube, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=708vzHBIiZY [accessed: 03.03.2025].

- 15T. Azevedo et al., Technical Note – Potential impacts of due diligence criteria on the protection of threatened South American non-forest natural ecosystems, MapBiomas, 2022. https://staging-brasil.mapbiomas.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/08/Nota_Tecnica_UE_07.07.2022.pdf [accessed: 03.03.2025].

- 16Marco temporal (Lei PL490/2007) – a law adopted by the Brazilian Congress on 30 May 2023. It assumes that new indigenous territories can only be demarcated in areas that were still inhabited by indigenous people when the Constitution was adopted in 1988. The new law therefore ignores the issue of forced resettlement and makes subsequent demarcation processes more difficult. The law also allows for the economic exploitation of indigenous lands and the possibility of establishing contact with peoples in voluntary isolation under the pretext of a not fully defined ‘public utility’. Câmara dos Deputados, Projeto de Lei PL490/2007, 2007, https://www.camara.leg.br/propostas-legislativas/345311, [accessed: 03.03.2025].

Leave a comment